The Viking Age (c. 800–1100) was a time of expansion in which Scandinavians settled in the Baltic Sea area and far beyond – even in North America.

Whenever treasures from the early Middle Ages are discovered within this vast cultural space, the question of attribution arises. To whom do they “belong”? Whose cultural heritage are they?

If we consult historical sources, we can see how multi-layered and sometimes contradictory the appropriation and attribution of such treasure finds can be. At different times they have been appropriated both as regional or national heritage, and also as European or world heritage.

“In Denmark we are proud of our Viking heritage – and for good reason. The Viking Age was an exciting time. It was a time when we bravely discovered new countries. I love it.”

Rane Willerslev, director of the Danish National Museum, 2021

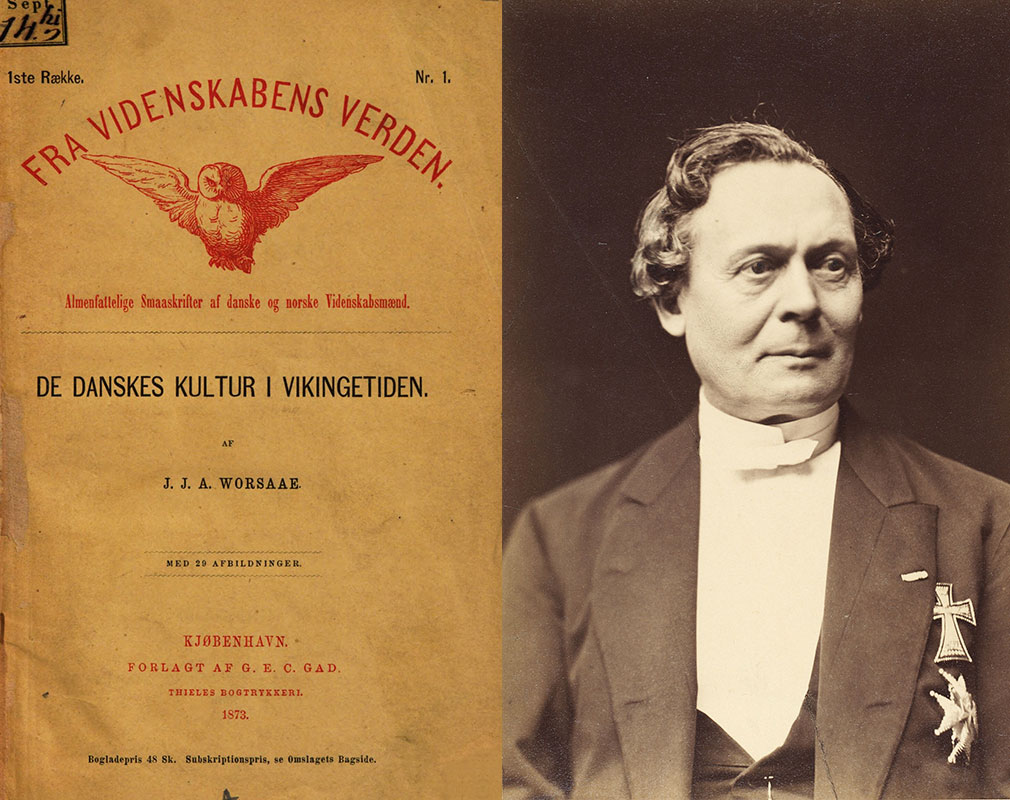

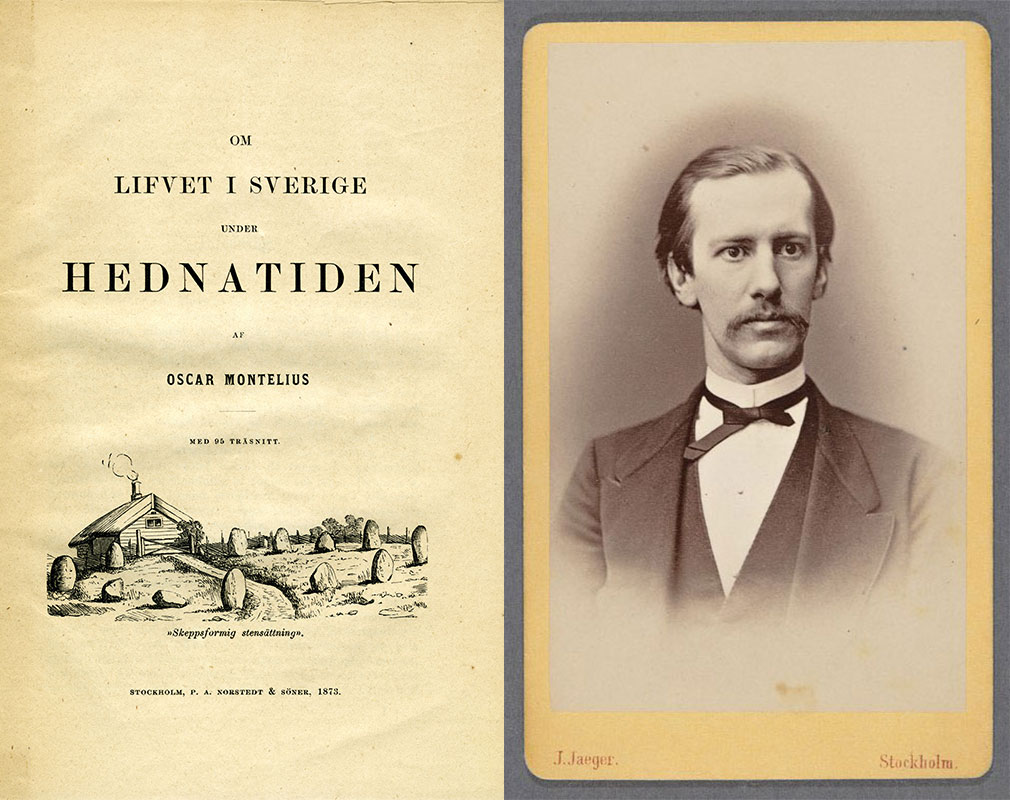

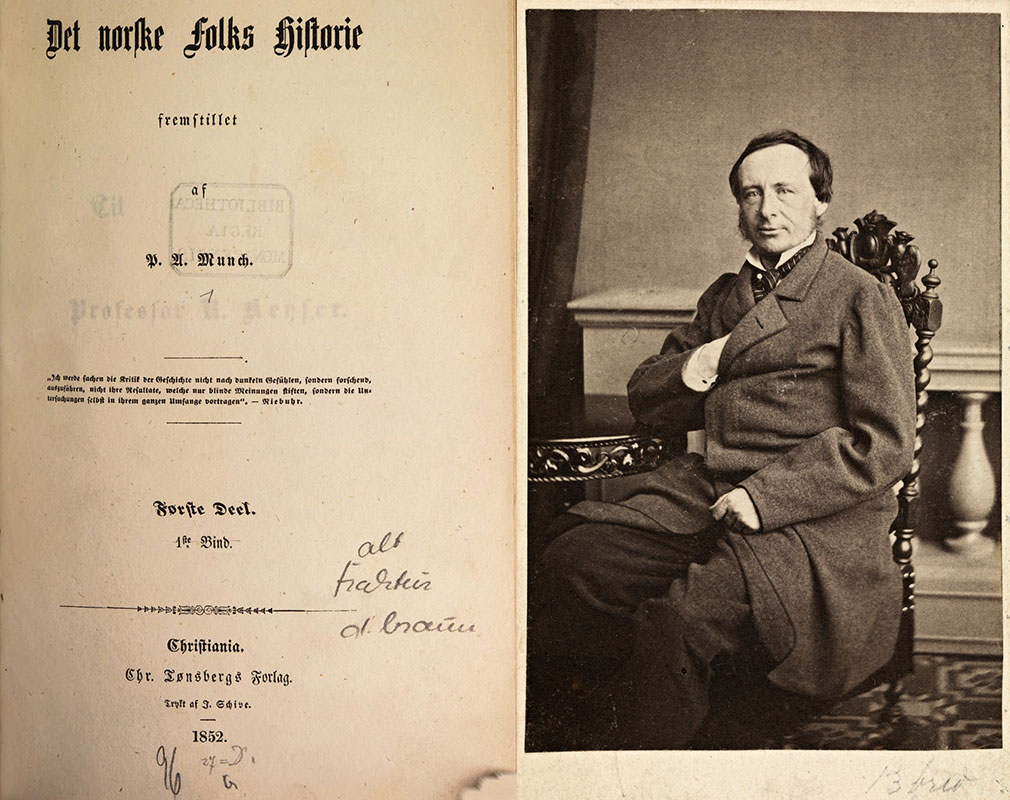

When the nation states of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden were created in the 19th century, archaeologists wrote new national histories for each of them. The period between pre-history and the Middle Ages was referred to as the Viking Age, after the waves of Scandinavian expansion. This era was believed to be the first time that these nations individually had an influence on world history.

The “new” age was integrated into the national museums: from 1904 onwards the Historical Museum in Oslo had its own Viking Age hall, with the Hoen Hoard as its centrepiece.

Even today, Viking-age objects are often presented in explicitly national ways in Scandinavian museums.

It is probably no surprise that Scandinavian finds such as the Hoen Hoard are appropriated for national purposes by the countries where they were found.

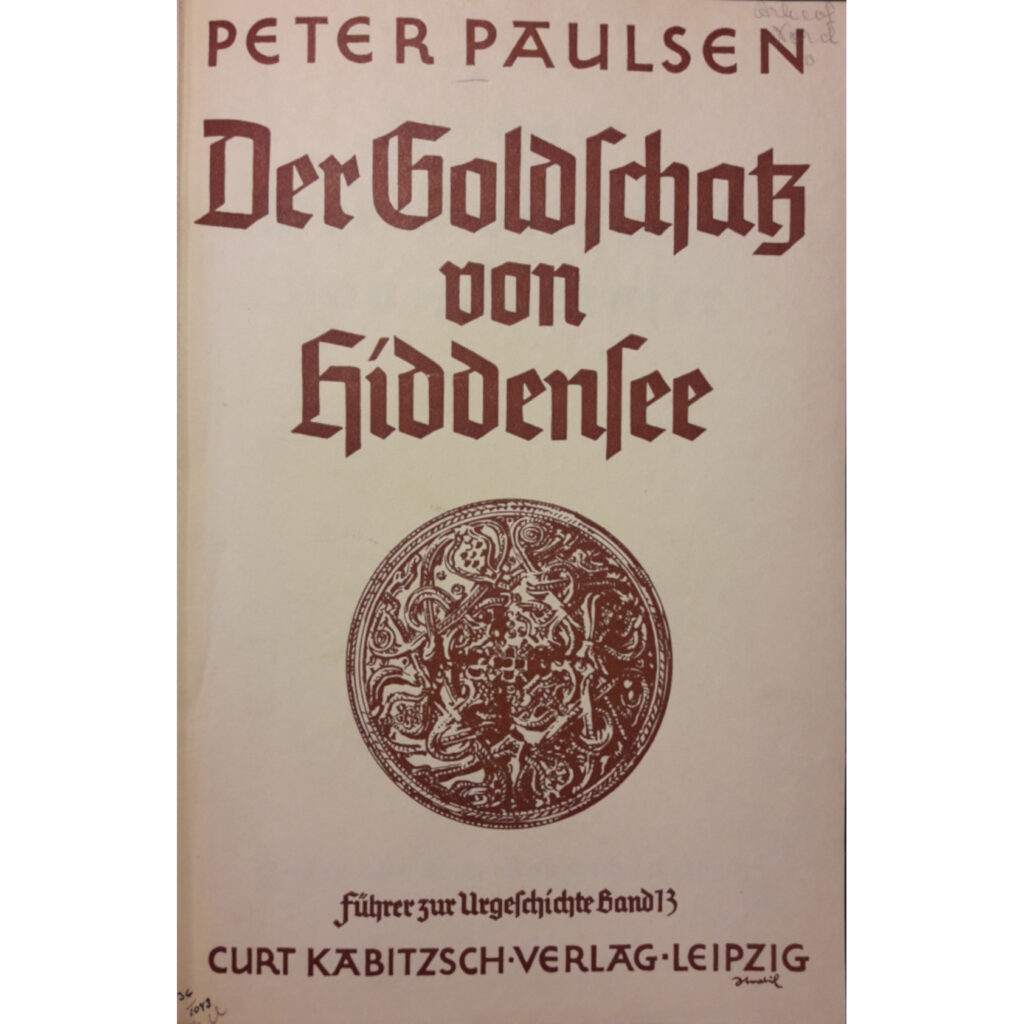

But even the Hiddensee Hoard was depicted as a part of national history – in this case, that of Germany – even though from quite early on it was assumed to be of Scandinavian origin.

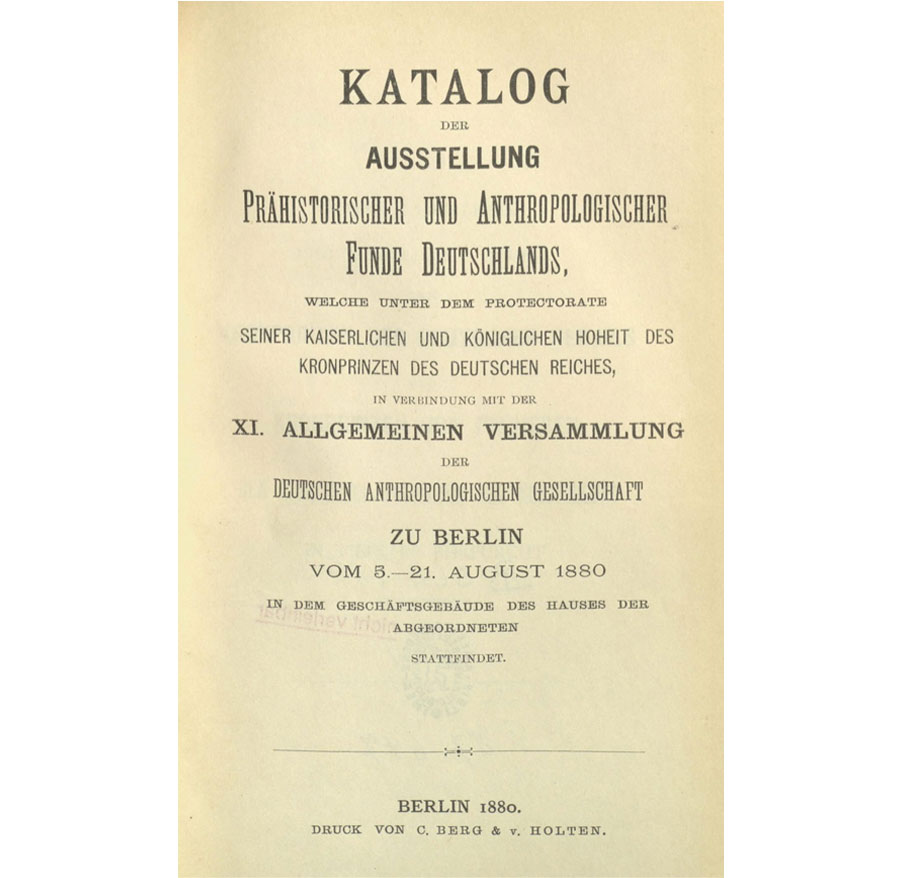

In 1880 it was put on display at the Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the German Reich.

In 1936 a replica of the Hiddensee Hoard was included in the Nazi propaganda exhibition Germany in Berlin.

From 1976 onwards it travelled around the world on a GDR postage stamp as an item of national heritage.

In the Scandinavian countries gold treasures from the Viking Age have always been valued as national heritage. Bringing together all finds of gold treasure in the museums of the capitals has contributed to their national appropriation.

By contrast, the Hiddensee Hoard ended up in a regional museum, connecting it with the region of Western Pomerania. In German exhibitions from 1880 and 1936 it was displayed as an item of national heritage, with an emphasis placed on its connection with the “Province of New Western Pomerania and Rügen” and later to the Nazi-era “Gau of Pomerania”. In 1936 the hoard’s Scandinavian origins were used to attest to an allegedly “Germanic” domination of the Baltic Sea region in Peter Paulsen’s publication.

However, the hoard also attained local significance in the region itself: In the 1920s, Stralsund goldsmiths started selling miniature replicas as jewellery. To this day, elements of the hoard can be found in souvenir shops throughout Stralsund and the surrounding area.

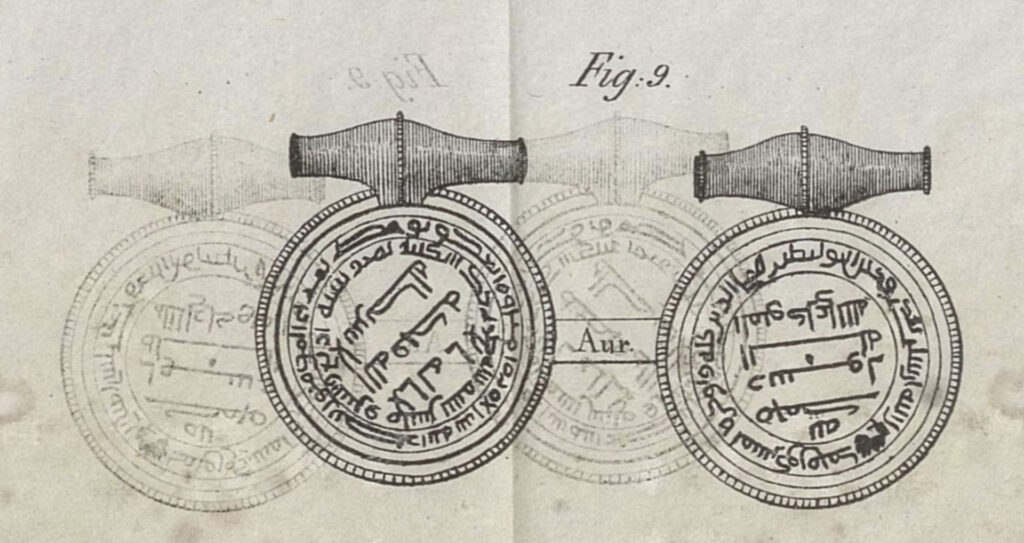

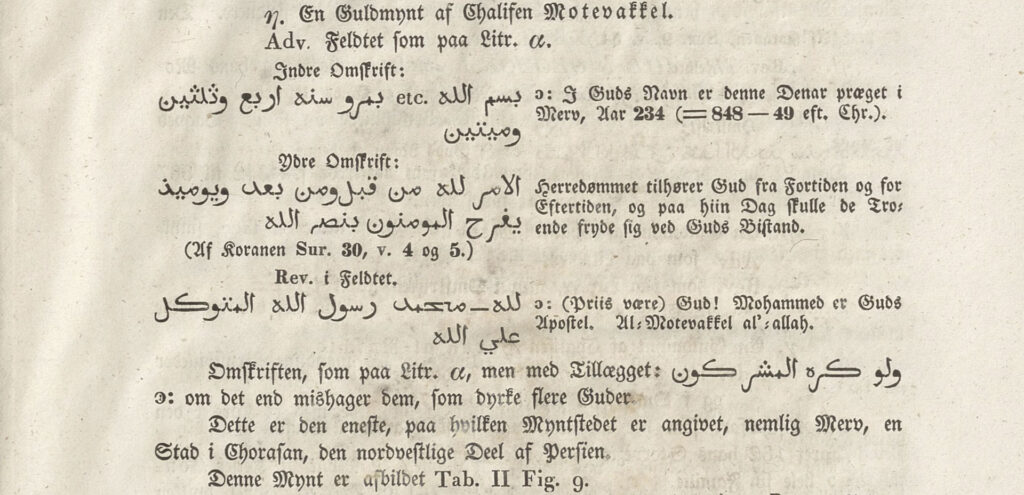

The geographically wide-ranging contacts established in the Viking Age were known early on. Not long after their discovery in 1834, some of the gold coins from the Hoen Hoard were recognised as being of Arab and Persian provenance. They were assumed to have reached Northern Europe via trading contacts.

However, this potential for writing history beyond national borders only started to gain recognition after World War II. In 1978 UNESCO, founded in 1945 for the purpose of increasing understanding among nations, included the Viking-age settlements in Canada in its list, as they represented “a unique milestone in human migration”.

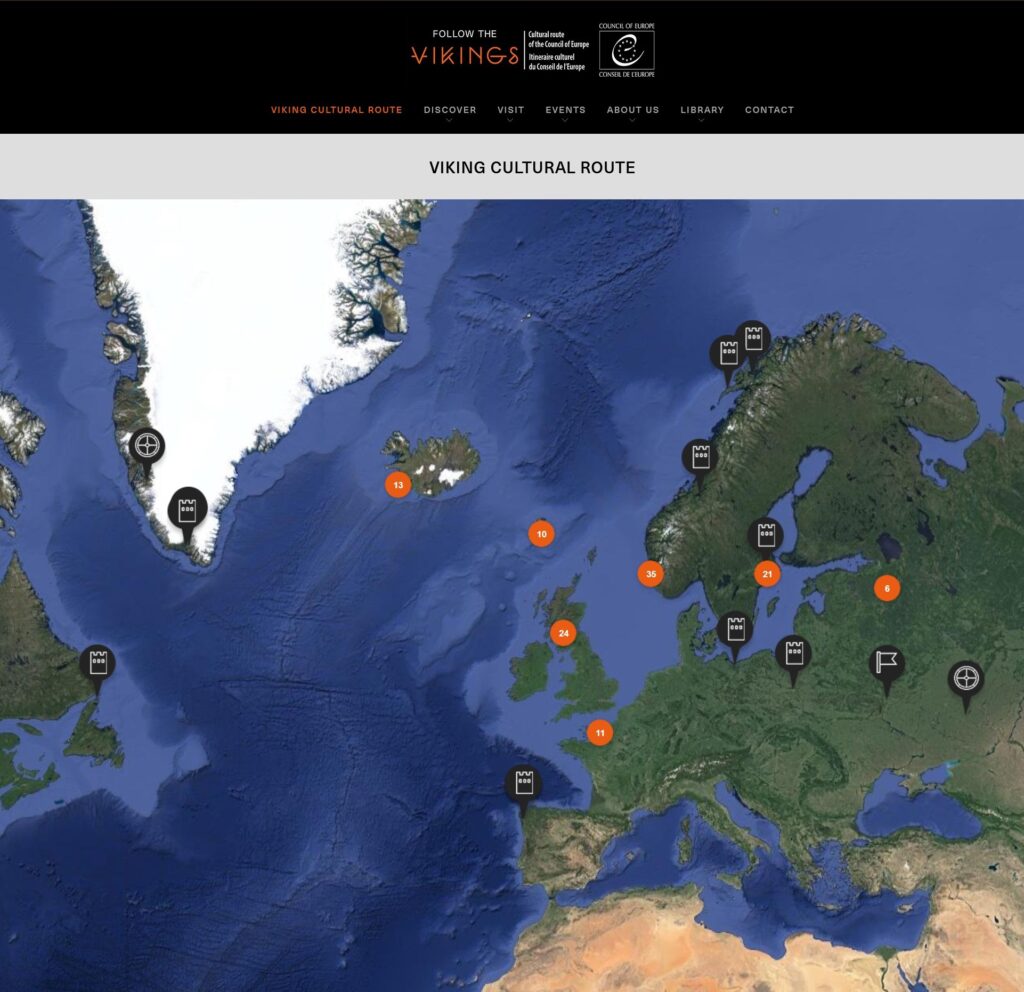

In 1993 the Council of Europe initiated the Viking Cultural Route, a travel route that encompasses not only various locations in Northern and Southern Europe, including Oslo‘s Museum of Cultural History with its Hoen Hoard, but also sites in North America and “the East”.

The Council of Europe’s website describes the reasoning for the project as follows: “At a time when few people travelled, the Vikings raided, traded, and settled extensively. For centuries they served as a vector for the transmission of culture and traditions throughout the European continent. The Viking heritage therefore unites the peoples of present-day Europe.”