Whether in goldsmiths’ studios or museum shops, at medieval fairs or on the internet, “Viking jewellery” is easy to find and extremely popular – among the global right-wing scene, too.

What does this link to Scandinavian early-medieval culture mean for those who wear it? Who adorns themselves with reproduction Viking-era jewellery; when do they do it, and why?

The reasons for this are complex, involving personal and political layers of meaning.

How would you wear the jewellery? What would it mean to you? Download the pendant and brooch and use them as stickers on a selfie.

You can post it on Instagram using the hashtag #myvikingbling on our profile

Bling it on!

“I have been attending Viking markets since early childhood, and I remember admiring the beauty of the Hiddensee jewellery whenever I saw someone wearing these pieces. I vowed to buy a copy for myself one day. As I grew up and learned more about the history behind these unique pieces, they became even more special to me. I will treasure them forever.”

On the back of the t-shirt there is an illustration of a pendant from the Hiddensee Hoard, accompanied by “Ultima Thule” and “Thor Steinar” in Runic writing. The fashion label is popular among right-wing devotees, blending an athletic style with references to Nordic folk culture and right-wing ideologies. These are often ambiguous: the brand name, for example, possibly combines the pagan Scandinavian god Thor with the SS general Felix Steiner. “Ultima Thule” was the ancient name for the far north of the world, but also recalls the nationalistic and anti-semitic Thule Society in the 1920s. The right-wing appropriation of Viking-era culture is based on the assumed superiority of “Germanic” heritage – in the Nazi period the Hiddensee Hoard was interpreted as evidence of a supposed “Germanic” domination of the Baltic Sea region.

“I originally gave my boyfriend a piece of jewellery as a present because his grandmother comes from the island of Hiddensee. Now I feel connected to his family and to the region through this jewellery.”

“I wear replicas of Hiddensee Hoard items above all because I like them and I’m interested in Viking-era symbols. I think they represent authenticity and an affinity to nature.”

This experimental contemporary re-imagining of the tenth-century queen Tove shows her adorned with the Hiddensee Hoard. It was one of a number of portraits created by photographer, designer, and practising heathen Jim Lyngvild, who had been commissioned by the National Museum of Denmark to present “the Vikings in a way that emphasises their humanity”, in the words of museum director Rane Willerslev. The museum initiated the collaboration in 2018 for the redesigned Viking-era section of its permanent collection. Critics expressed concern that these fictional images might be mistaken for archaeological reconstructions.

The Ding-Spiele in 1930s Germany were semi-religious theatrical performances inspired by Viking-era myths, of the kind that have been handed down in the Edda. The Nazi ideology propagated the notion of an extreme inequality between different people, with the “Aryans” ranking right at the top; apart from the Germans this primarily included Scandinavians. Nobody seems to have had a problem with the fact that the costumes in the photo had little to do with the Viking era – Bronze Age lurs (blowing horns) and women’s jewellery were mixed in with Viking-era myths in order to construct an Aryan Germanic “heritage”.

According to a plaque on the casket, this replica of the Hiddensee Hoard was gifted to the East German head of state, Erich Honecker, in 1973, when he gave a speech at an annual festival called the Ostseewoche. It was presented by the local leadership in Rostock of the East German ruling party, the SED (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands). The replica made of solid gilded silver was presumably never worn because the cast pendants are not pierced through. Unfortunately, there are no clues about whether and how Erich Honecker used “his” Hiddensee Hoard. The aim of the Ostseewoche was to enhance East Germany’s diplomatic relations with other Baltic states, so the replica jewellery probably symbolised the long history of exchange in the region.

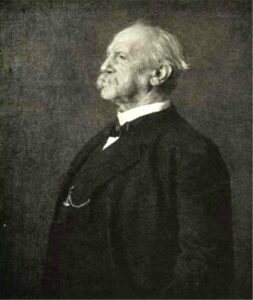

In this painting, the influential Swedish archaeologist Oscar Montelius (1843–1921) is wearing a reproduction “Thor’s hammer”. Many pieces of jewellery like this have survived from the Viking era, predominantly as part of treasure hoards or individual finds, or from women’s graves. Montelius conducted a great deal of research on the Bronze Age in Europe and the Near East; in 1898 he wrote an essay on Bronze Age and Viking-era depictions of hammers. Photographs reveal that he also wore “his” hammer in everyday life. In this portrait, taken late in life, he clearly found it important to stage himself with a Thor’s hammer, perhaps as a symbol of his activities as an archaeologist.

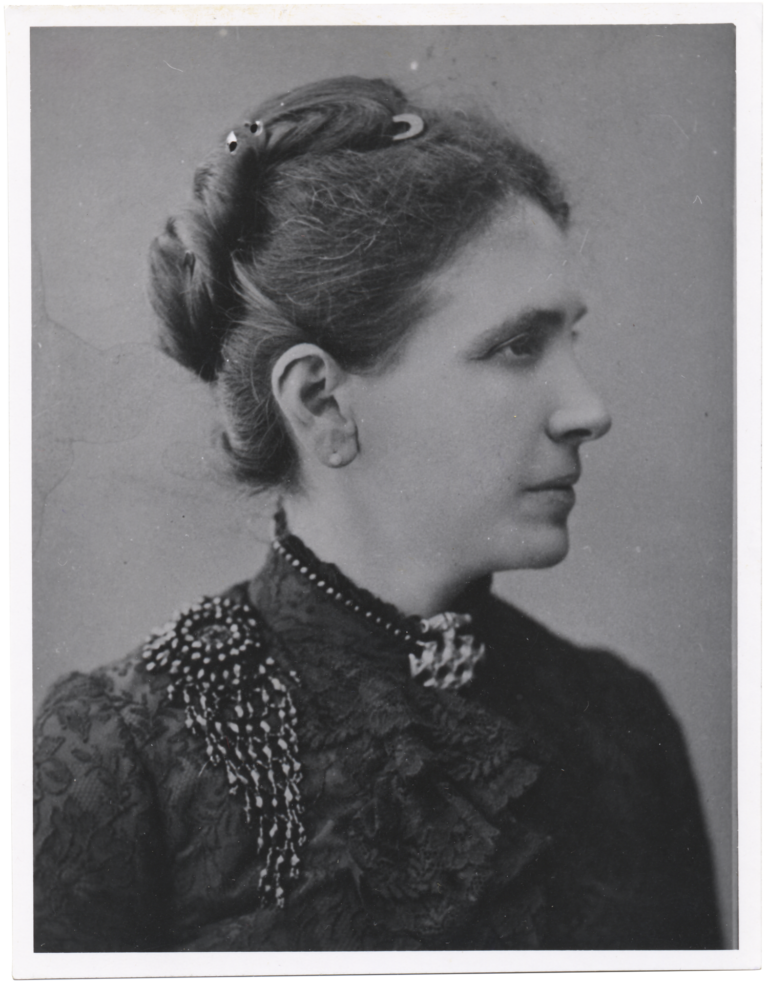

Sophia Schliemann, the wife of businessman and archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann (d. 1890), is shown here with a replica item from the Hiddensee Hoard resplendent around her neck. Another portrait of the young Greek woman has become more famous. It shows her wearing part of Priam’s Treasure from Troy, which her husband had been involved in excavating. Very few people know about this other picture from the estate of Schliemann researcher Ernst Meyer (d. 1968). A note on the reverse comments that the subject was already a widow at the time. The Viking-era jewellery links her to her husband’s home region of Mecklenburg.

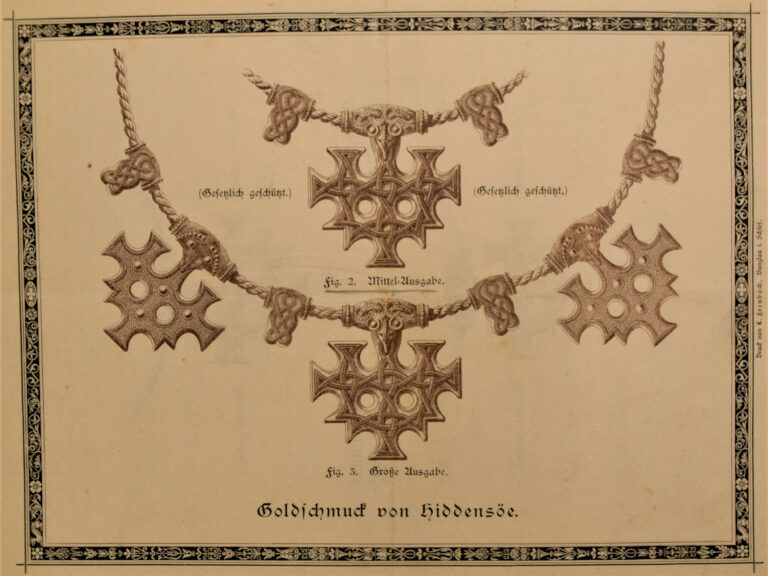

Not long after the discovery of the Hiddensee Hoard between 1872 and 1874, replicas were being produced as costume jewellery. In this advert dating from 1 May 1882, goldsmith Paul Telge touts his “most beautifully executed reproductions”. The pendants were primarily designed as what the leading women’s fashion magazine Der Bazar called a “highly tasteful gift for younger and older ladies”. According to the 1883 conference report of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte, many female members of the association wore the jewellery, too.

The operatic bass Joseph Niering (d. 1891) is dressed as a typical Viking in the role of Hunding from Richard Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungen. The nineteenth-century image of Vikings as warriors wearing horned helmets and drinking mead is still popular today – but it was dreamed up by Wagner productions, among other things. Researchers present a different picture: Viking-era culture was not merely the product of warriors. Women also played key roles in society, and agriculture and artisanry – such as goldsmithing – were practiced with great skill.

This photo of members of Swedish high society dressed as “Vikings” was taken in 1869 at a fancy-dress ball in Stockholm. In wearing the clothing, weapons, and jewellery that accorded with their own age’s ideas about the Viking era, they were establishing a relationship with their ancestors. At the time, the reference to the Viking era was closely associated with Swedish nationalism: between 1811 and 1844 the patriotically minded society Götiska Forbundet sought to revive what were thought to be ancient Swedish customs by drinking from horns and calling each other Old Norse names. A few decades later this had apparently become acceptable practice in high society too.