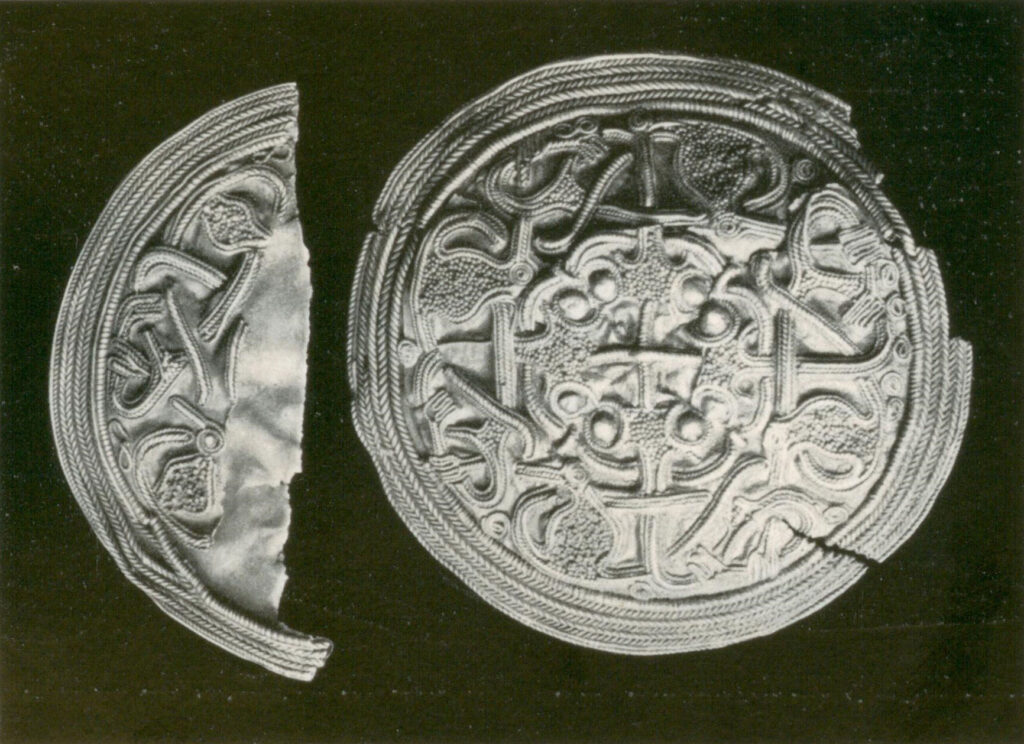

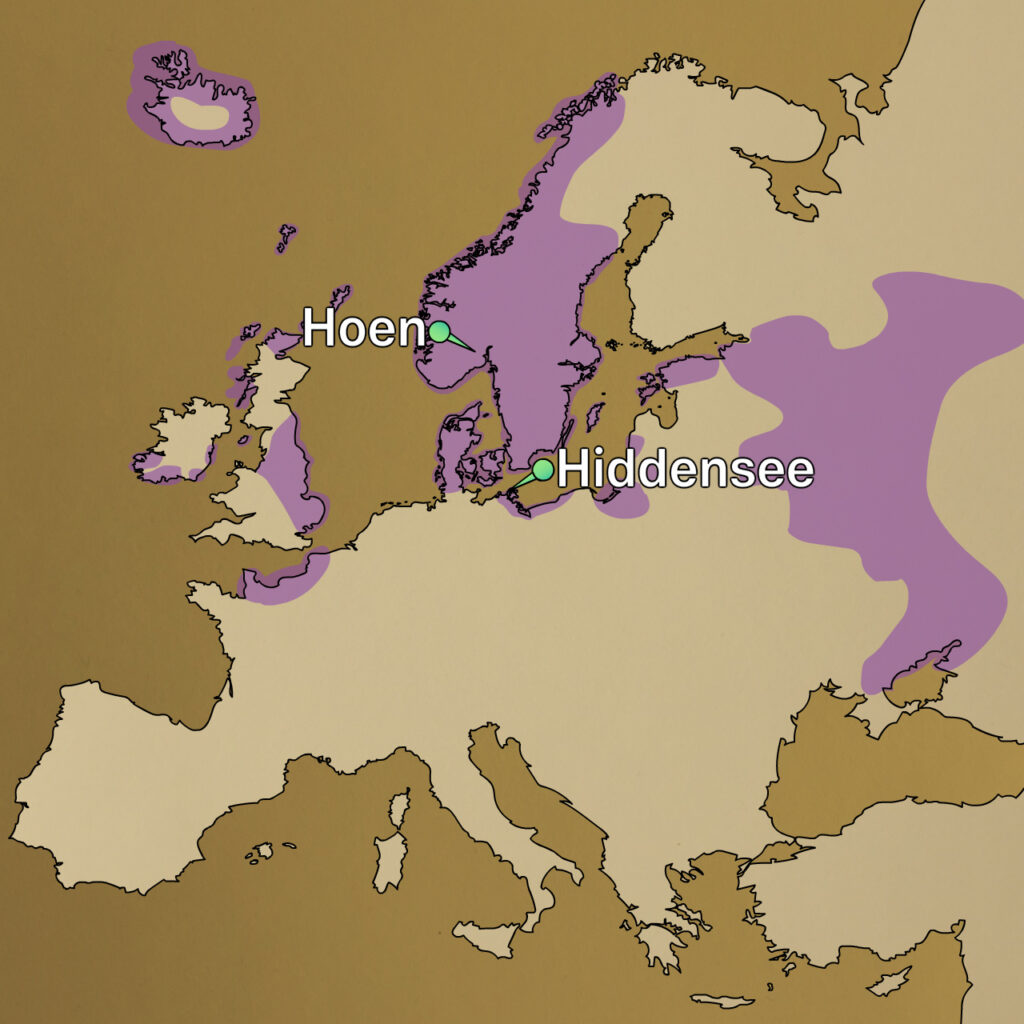

The Hiddensee Hoard consists of 16 pieces: 14 pendants, a neck ring, and a disc brooch. The items contain gold of an almost identical chemical composition, and the quality of its technical execution is outstanding. The jewellery was created by an experienced goldsmith in the late 10th century, subsequently buried on the north German island of Hiddensee, and not rediscovered until 1872–74 after several storm tides.

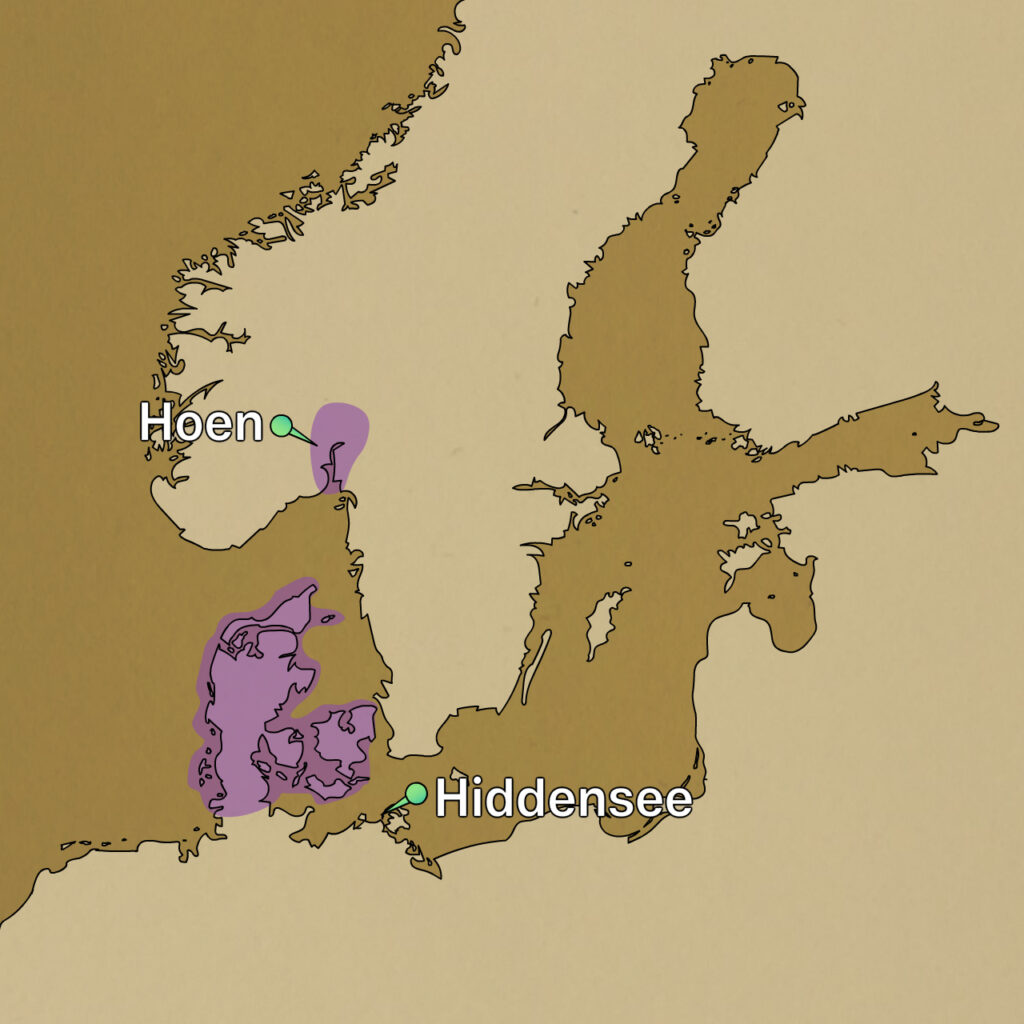

Weighing 2.5 kg, the hoard, which was discovered in 1834 in a field belonging to Hoen farm in south-eastern Norway, is the largest surviving Viking-age gold hoard. Unlike the Hiddensee Hoard, which is of uniform technical and stylistic execution, the Hoen Hoard consists of 207 individual components, including Byzantine glass beads and coins from the Islamic world. The provenance of the various parts testifies to the wide-ranging network of Scandinavian elites in the late 9th century.

The Hiddensee Hoard belongs to a group of jewellery in the “Hiddensee style” dating from the second half of the 10th century. Press models for making disc brooches and pendants in this style have been found in Haithabu, the most important port in the Danish Kingdom, and the ringforts built under Harald Gormsson, known as “Bluetooth” (d. 986/7). They indicate that the jewellery was created within the sphere of influence of this Danish king.

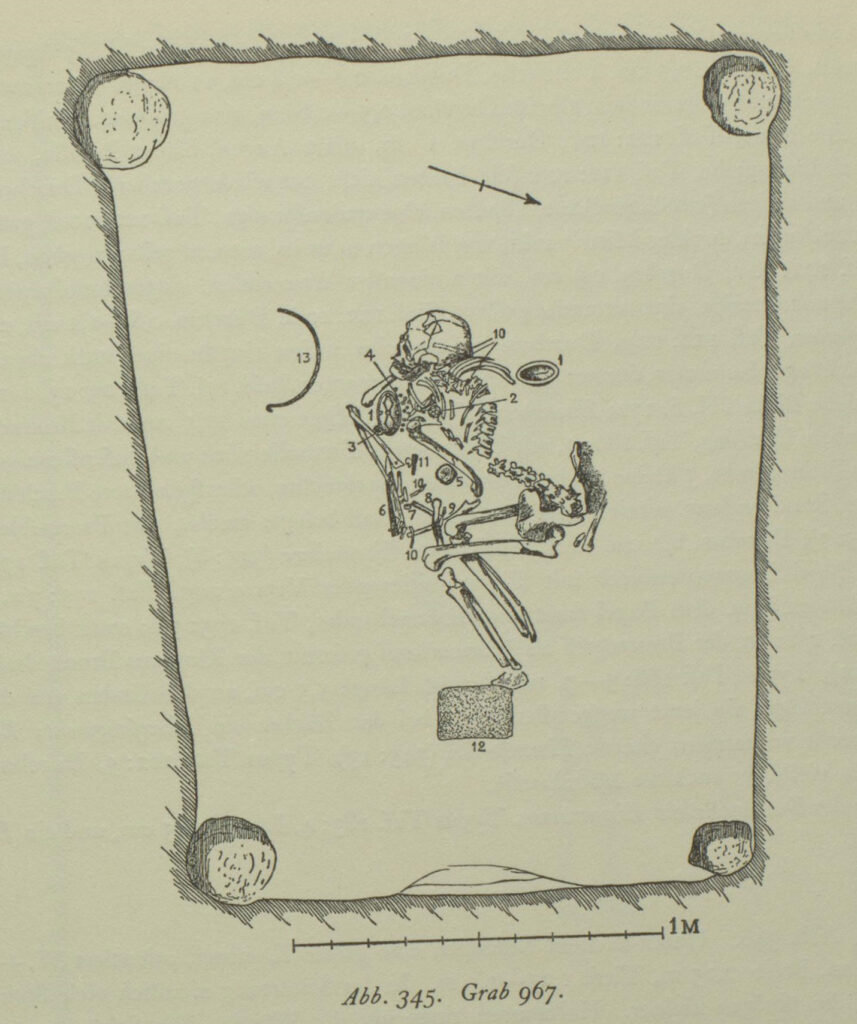

Given that Harald was baptised in 960, the cross-shaped elements on the brooch and pendants of the Hiddensee Hoard might well have a Christian connotation. However, the king did not wear the jewellery himself. Disc brooches found alongside female skeletons suggest that the Hiddensee Hoard, too, was probably women’s jewellery.

The imported coins and other components of the Hoen Hoard were fitted with loops in a Scandinavian goldsmith’s workshop in order to convert them into pendants. They probably served as a necklace that signified the status of a powerful figure.

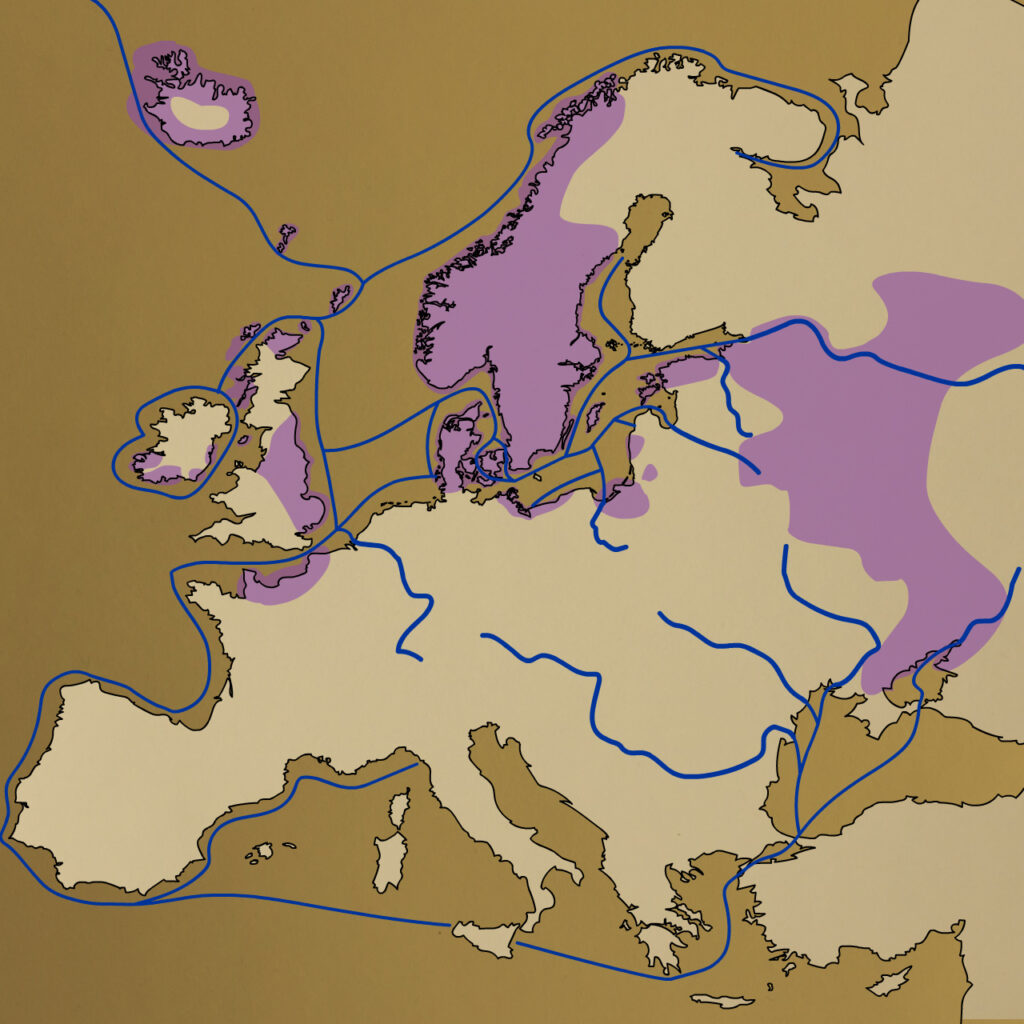

The 9th century was a time of Scandinavian expansion involving expeditions and looting all over Europe. The area where the hoard was found had good links to local and long-distance trade routes. The owners of the hoard probably benefited directly or indirectly from this expansion.

Neither gold nor silver was mined in the Baltic Sea region during the early Middle Ages. Viking-age Scandinavian jewellery was made from imported objects – for example coins that were melted down and reused.

Many thousands of kilograms of silver found their way to northern Europe via trade routes. The metal was traded in exchange for desirable products (such as furs), but also for enslaved people. An estimated 400,000 Arabian silver coins, sometimes broken up into “hacksilver”, have been found and suggest that imported silver was used for everyday business transactions in the Baltic Sea region. Even cheaper items could be paid for with coins that had been cut up to produce pieces of a specific weight.

Finds of gold, on the other hand, are rare, and those that do occur often survive undamaged in hoards. Gold does not appear to have played a role in trade.

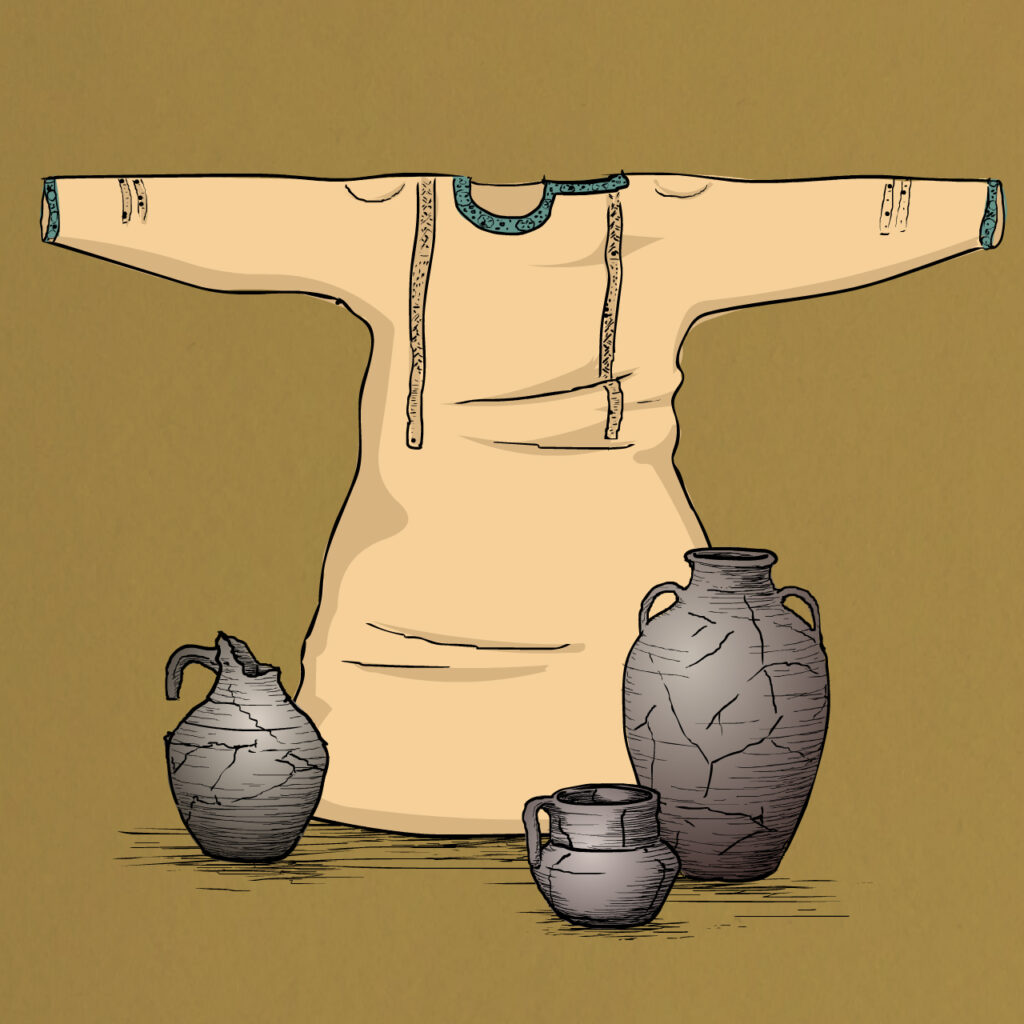

Individual gold objects may have come to Scandinavia as gifts. This practice is documented in a report by Al-Ghazal, an Andalusian diplomat who brought gifts of clothing and vessels to a Scandinavian ruler in 845.

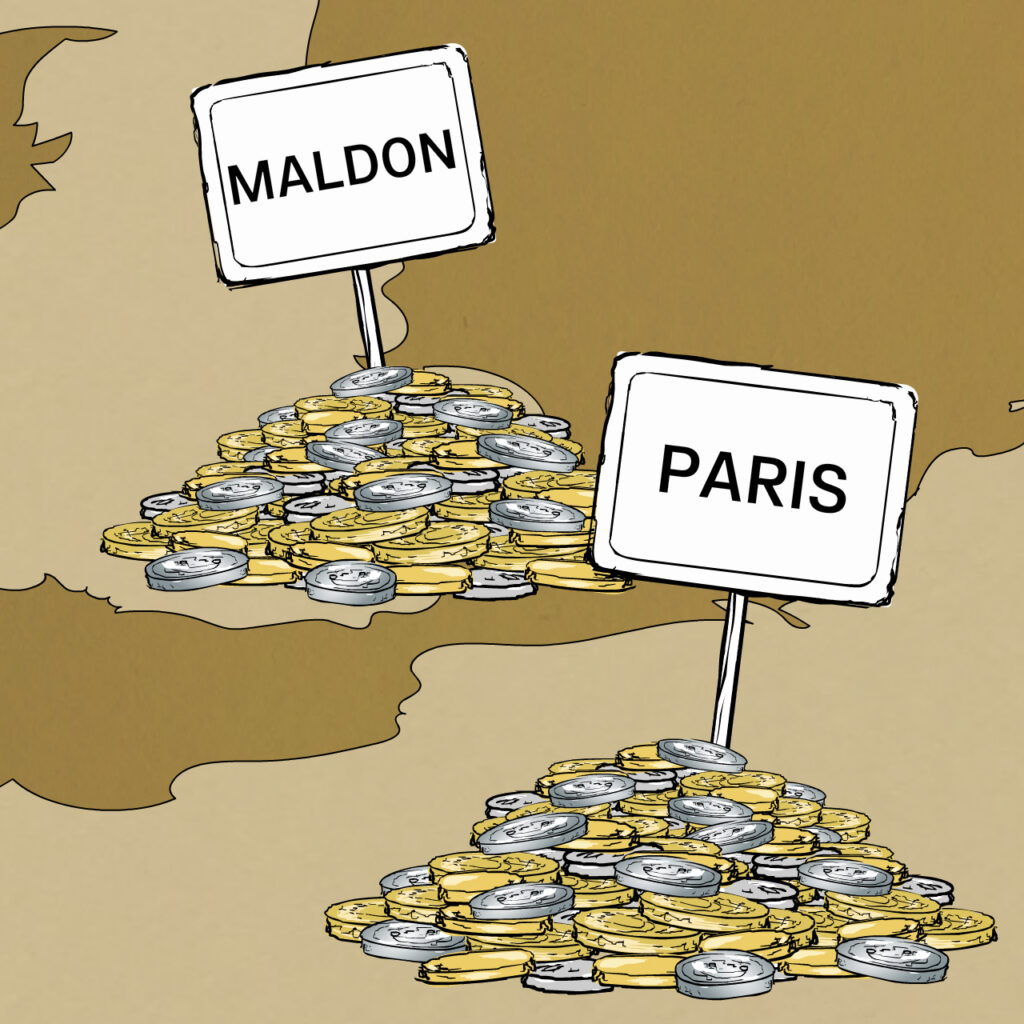

However, a large proportion of the gold that was processed in Scandinavia seems to have been acquired through tribute payments and raids.

For example, Frankish chronicles note that the Viking leader Ragnar received a ransom of 7,000 Frankish pounds of gold and silver after the attack on Paris in 845. In 991, an agreement with King Ethelred after his defeat in the Battle of Maldon stipulated the payment of 22,000 pounds of silver and gold to the victorious Scandinavians.

In the Viking-age Baltic Sea region, gold and silver served various different social purposes. While large amounts of silver were in circulation as currency, gold was reserved for the highest social classes. The Hiddensee Hoard belonged to one or more women who were close to the king.

A comparison of the Hiddensee Hoard with the almost 100 other found items of jewellery in the Hiddensee style illustrates the extraordinary nature of the hoard: while the the large cross-shaped pendants from the Hiddensee Hoard measure almost 7 cm, the comparison items are smaller and predominantly made of silver. Owning and displaying gold jewellery was a sign of power.

Its uniform design may mean that all jewellery in the Hiddensee style should be linked to the Danish court. The Old Norse literature of the Middle Ages also indicates that Viking-age Scandinavian rulers distributed golden armrings as gifts to secure the loyalty of their minions and to consolidate political ties.

The archaeological evidence reflects the fact that women probably played a special role in this game of treasure politics, for example through diplomatic marriages. The dissemination of Hiddensee-style disc brooches, which were worn exclusively by women, is attested in the Baltic Sea region by findspots extending into modern Poland and Russia.